SYSTEMIC PROBLEM:

Poverty & Money Bail

Introduction

In the U.S., the money bail system places a financial price on freedom. People accused of crimes can go free while awaiting trial if they pay a set bail amount. But for those struggling financially, even a small bail amount can lead to devastating consequences. This creates a two-tiered system: one for those who can afford to pay, and one for those who cannot.

The Problem: Punishing Poverty

Late one night, John and David are arrested separately for the same nonviolent property crime. They are hard-working men, both supporting their families working 9-to-5 jobs. When the judge sets their bail at $1,000 each, their experiences diverge.

John posts bail and returns home within hours. He continues to work, support his family, and prepare his defense from home. His routine is barely interrupted, aside from attending court dates.

David, however, cannot afford to pay $1,000. His absence from work causes him to lose his job. His wife, already stretched thin, picks up extra shifts at Kroger but still cannot cover rent and food. Two weeks later, an eviction notice is taped to their door, plunging them into further instability and poverty.

Both men are accused of the same crime and have not been found guilty. Yet while John carries on with his life, David’s family is torn apart—all because one has cash, and the other does not.

The Real World: Two Shelby County Arrests

These stories are not hypothetical. They reflect real arrests for the same level of nonviolent property crime in Shelby County.

Booking #21100602: This person, unable to post their $1,000 bail, spent 244 days in jail during the COVID pandemic before being released.

Booking #21117320: With the same bail amount, this person posted it immediately and was released the same day.

Though both men attended all court dates and ultimately had their charges dismissed, the damage was done. For one, freedom came at minimal cost. For the other, their financial circumstances were punished long before a verdict.

The Data: How Small Bail Amounts Impact Our Community

In this section, we explore how even small bail amounts of $1,000 or less disparately impact the people in our community struggling financially. To do this, we take two approaches for estimating a defendant’s financial status with our data: attorney appointment and home zip code. For detailed information on the data used in this section, see the Appendix at the bottom of the page.

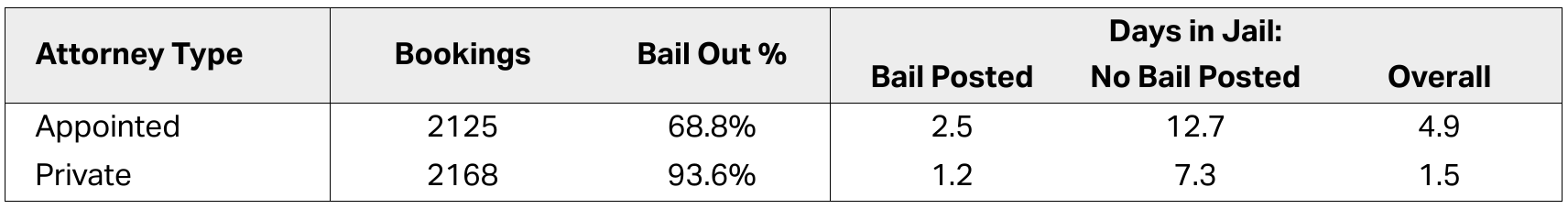

Approach #1: Attorney Appointment

If a person is not able to afford an attorney, the court appoints one to represent them, usually a public defender. Therefore, if an attorney is appointed to a case, it is a good indicator that the defendant is struggling financially, and we can use that data to compare metrics between people who are able to afford an attorney and people who are not.

Key Takeaways:

98% of people with private attorneys post bail and are released in 1.2 days on average.

Only 70% of people with appointed attorneys are able to post these low-level bails, and the 30% who can’t remain in jail for an average of nearly 10 days.

Approach #2: Zip Code

Alternatively, by restricting the bookings to Shelby County residents and looking at the poverty rate in the defendant’s home zip code, we can see a similar trend: people who come from areas with higher rates of poverty post low-level bails less often and — when they are able to — more slowly than people from wealthier zip codes.

Wealthier Zip Codes Post Bail More Frequently and Quickly

Key Takeaways:

People from wealthier zip codes are more likely to post bail quickly.

In impoverished zip codes, posting bail takes longer and are less likely to be able to post bail at all.

Conclusion:

These analyses reveal a troubling trend: economically disadvantaged people struggle to secure timely release compared to their wealthy neighbors despite committing similar crimes. This disparity underscores the urgent need for policy reforms to address the systemic inequalities that disproportionately harm marginalized communities and people struggling financially.

-

Our database is primarily built from the information contained in two data sources: theShelby County Criminal Justice Portal and theJail Roster. Through many hours of work, we have developed a system of collating and cross-validating the data shared between them. Despite our strong opinions on criminal justice, we have equally strong opinions regarding integrity, and we strive for our data analysis to meet that standard. Questions, concerns, and corrections are sincerely welcomed by our Data Scientist (ryan@justcity.org) and will be addressed as quickly as possible.

Zip Codes: Zip codes were extracted from addresses by pulling the trailing digits/hyphens from each listed address and keeping only the first 5 digits to remove the “plus-four codes” when given a 9-digit zip code. Entries with invalid zip codes (e.g. 00000 or 1234) or incorrect zip codes (e.g. addresses with cities in Shelby County, TN with a zip code not associated with Shelby County) were then searched using a Shelby County ArcGIS API endpoint. Of the 369k addresses in our database, approximately 36k or 10% required search and 33k found a valid match. For the people who have more than one associated address, we choose the zip code associated to their most recent. There are approximately 40 bookings where the address associated to that person indicates homelessness like 201 Poplar (Shelby County Jail), 590 Madison (Hospitality Hub), 383 Poplar Ave (Memphis Union Mission), or 166 Poplar Ave (First Presbyterian Soup Kitchen). Some people also just listed "Homeless" or "Unknown" with an erroneous zip code. These zip codes were replaced with "HOMELESS" which was assigned a 100% poverty rate in the plot.

Attorney Appointment: We say that a person has an attorney appointed to their booking if Odyssey indicates that any case on that booking has indications of an attorney appointment. To do this, we look at two places on the Odyssey case profile: First, if the attorney listed in the Attorneys section of the page is labeled as a "Public Defender". Second, we look at the Case Events section to see if "Public Defender Appointed", "Public Defender Relieved", "Court Appoints Attorney", or "Private Attorney Appointed" are events that appear.

Bookings: We refer to a stay in jail after an arrest as a “booking”.The analyses above consider the 6,742 bookings after January 1, 2021 through July 14, 2024 with bails posted between $1 to $1000. Our intent with this analysis is to accurately portray the difficulty of posting low-level bails, so we then filter this superset of bookings to increase the cleanliness and interpretability of the analysis while decreasing the risk of bias, resulting in a final dataframe of 4,293 bookings. The following is a list of issues we encountered with notes on how they biased the results and how we mitigated that problem to obtain this final subset of bookings.

Important Note: The trends shown in the above analysis are not affected by any of the following cleaning, and in fact, these alterations generally bias the results against our thesis to make disparities appear less severe.

There are 438 bookings that have a higher bond (larger than $1,000) for a significant period which then gets reset to a low-level bail that the defendant is able to afford. If we just looked at the bail posted amount and not the history of the bail settings on the booking, this would make it look like a person couldn’t afford a small bail for a long period of time. While this naive conclusion aligns with the claims of this article, we are only interested in quantifying the true disparate impact of money bail on people struggling with poverty. Therefore, we only include bookings where the primary bond set and bond post are both less than $1,000

Many of the longest jail stays at this low level of bail have cases in which the person is undergoing “Mental Evaluation”. For example, Booking #20202807 was arrested for Disorderly Conduct, a Misdemeanor C which carries a maximum punishment of 30 days in jail or a fine of $50 or both. After the judge set a bail of $50, this woman spent 344 days in jail — far beyond the maximum punishment for the alleged crime — until she was able to post bail. The case events during this time are primarily “Mental Evaluation”, and while jail is a place which can severely exacerbate mental health issues, we are not familiar with the nuances of the situation and do not want these instances to unfairly increase the average days spent in jail on low-level bail amounts. Therefore, we drop the 138 bookings where “Mental Evaluation” appears on an associated case.

When a booking has multiple sets of charges and cases, there can sometimes be pre-set bonds or hidden factors holding a person in jail unrelated to the bail amount — such as Violation of Probation. While we can detect this with a relatively high degree of confidence, we believe that these more complex instances potentially obfuscate the simple comparison that we want to make here. Therefore, we do not include the 626 bookings associated with more than one set of charges or events.

Some cases have been expunged (i.e. erased) from the public data sources before we were able to determine if bail was posted, an attorney was appointed, etc… so we drop the 5 bookings that have expunged cases or do not have a clear reason for their release (e.g. bail was posted or the case was dismissed a few days before the person was released from jail).

There are many instances in which a person is booked and then the case is disposed within 48 hours which biases the “Bail Post %” to look worse than it really is because the defendants do not have time to post their bail before resolving their case entirely. It is also important to note that dropping these instances increases the average length of time spent in jail before posting bail, but we believe the analysis results in a more accurate picture of their length of stay in jail due to unaffordable bail. Therefore, we drop 312 bookings in which the final disposition date of the cases associated to the booking is less than two days after the person is arrested. Again, all of these scenarios create the illusion that some people cannot afford their bail, when in fact it is simply because they did not have time to post their bail before their case was closed. We applaud judges quickly dismissing frivolous cases.

A person can be rearrested on the same charges due to bail conditions, failure to appear in court, or other scenarios. These situations are often outliers when compared to the typical situation when someone is arrested on new charges which is what most people think of someone being arrested. Therefore, we only keep bookings where the person is arrested on a new set of charges, dropping 2,331 bookings.

For the analyses breaking out metrics by Shelby County zip code, there are 619 bookings in which the person associated to the booking either does not have a valid address or does not have a Shelby County zip resulting in a final count of 3,294 bookings for these statistics. This factor does not affect analyses grouping by attorney appointment because those are agnostic of residence.

X number of bookings do not have a case with any attorney information listed on the profile including the name of the attorney or indications of attorney in the Case Events. These bookings are dropped for the "Attorney Appointment" analysis approach.

Scatterplots: Each scatterplot in this article is accompanied with a “line of best fit” computed through unweighted “ordinary least squares” (OLS).

Poverty Rates:

The poverty rates of zip codes were calculated with data from the Census Bureau’s 2021 American Community Survey 5-year Data. While using both zip code poverty rate and Public Defender appointment rates may not have been necessary, we wanted to highlight that using distinct sets of data yielded the same results.